The German shortage of skilled workers and how we can counter it

Jill Hollender, Founder & Managing Director at Shadow Your Future

Dr. Manfred Mohr, Second Community School Dean at Karlsruhe University of Education

The shortage of skilled workers in Germany is also currently evident in many areas. It is no longer just the sectors in the skilled trades, industry or technology that have been poorly supplied for years that are affected. Triggered by shifts in the corona pandemic, new or worsening bottlenecks have emerged, for example in the hospitality industry or the security sector. At the same time, the demand on the training market is being met by an increasing number of young students who are undecided or have little orientation. The aim of the following article is therefore to highlight the status quo of the gaps in the training market and at the same time to show the background and explanatory approaches to the career choice behavior of young people. Furthermore, the experience of the start-up „Shadow Your Future“ will be discussed, which offers an adequate solution in the context of career orientation and securing young talent.

Current figures on the number of vacant training positions illustrate the difficult situation on the German training market. After an initial downward trend in the number of reported training positions, these reached a level of around 440,000 vocational training positions between October 2021 and March 2022. This corresponds to an increase of seven percent compared with the same period of the previous year. The number of in-company training places also rose by 7 percent compared with the number of training places offered outside companies. In purely arithmetical terms, there were therefore around 130,000 more training places than registered applicants. Particularly large numbers of vacant training places are currently to be found in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saarland, Thuringia, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. In fact, 297,700 training positions in companies were still unfilled in Germany in March 2022. This represents an increase of 15 percent over the previous year (Bundesagentur für Arbeit 2022).

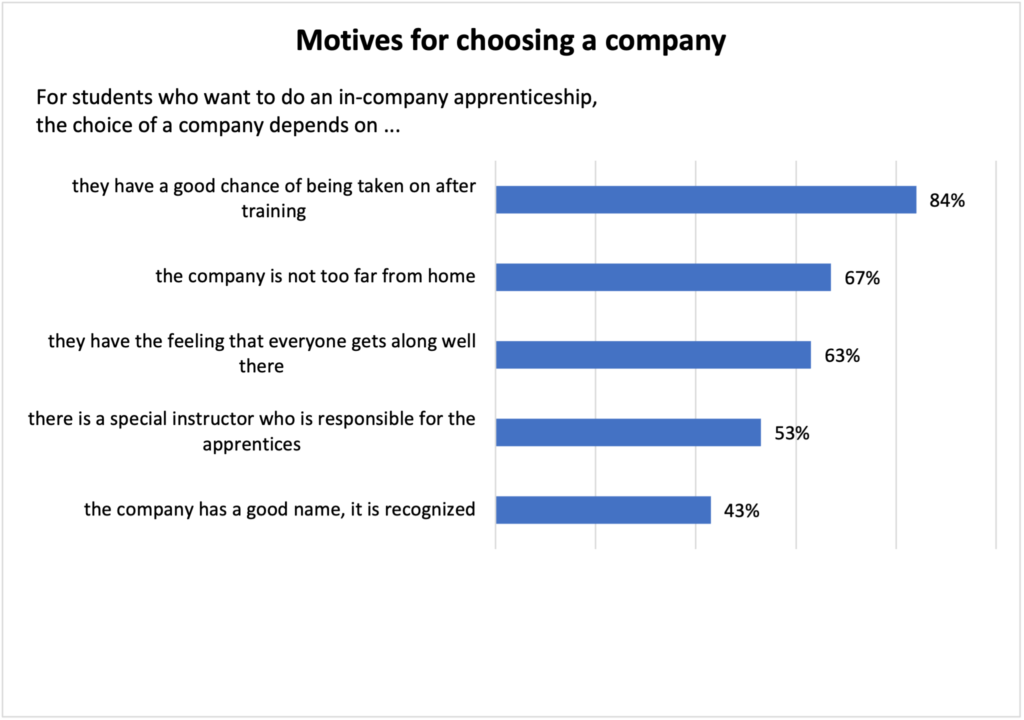

Areas particularly affected by the shortage of skilled workers are the healthcare industry, the construction industry, the hospitality industry and the STEM sector (DIHK 2021, Anger et al. 2021). For the future in an Industry 4.0, a further increase in demand and a strong supply surplus of jobs are emerging (Hüther 2017). At the same time, the growing shortage of skilled workers poses a threat to Germany’s innovative strength as a business location. For the realization of future projects in housing construction, climate protection, infrastructure and digitization, however, all players involved are dependent on the availability of sufficient well-trained personnel. A majority of companies are therefore in favor of increasing wages and, on the other hand, would also like to offer the possibility of more flexible and mobile working. The focus is also particularly on aspects to improve the work-life balance and facilitate the integration of immigrant foreign specialists. Almost every second company also sees particular opportunities in increasing their training efforts (DIHK 2021). Today, training companies are making more frequent and earlier use of the training placement services offered by the Employment Agency. The picture among young people is exactly the opposite. They are not only using the training placement service later, but also less frequently than in previous years (Bundesagentur für Arbeit 2022). The reason for this decline is believed to be the limited opportunities for personal and direct contact during the Corona crisis. For a certain period of time, internships were only possible to a limited extent, or were even prohibited in some sectors. Numerous training fairs were cancelled, and direct contacts at school were hardly possible (Fitzenberger et al. 2022). Accordingly, using newer ways of communication and contact mediation could be a target-oriented project for companies. At the same time, indirect contact via smartphone and social media is also increasingly in line with the young target group of Generation Z youth. More than three quarters of 14–29-year-olds use YouTube as an information channel. About 50 percent use Instagram and Facebook to get information, and more than a quarter also find out about a growing number of topics on TikTok (Schnetzer 2021). For career choices, however, parents and conversations with peers appear to be the two most important sources of information, followed by information from the Internet (Köcher et al. 2019). Overall, despite newer and additional options, a significant need for career information can be assumed. This is because, at the same time, the multitude of information and opportunities makes it more difficult for adolescents and young adults to make career decisions (ibid.). The need for security, which a certain training company can guarantee, proves to be very important for career choice decisions. Another important factor is the desire to find a training company as close to home as possible. Other important points are found in the emotional area, such as the feeling that everyone there gets along well and having a personal contact person who is there for the apprentices. The image of the company is only ranked fifth (Calmbach et al. 2020).

From a scientific perspective, models of career choice can be divided into psychological and sociological approaches (Dreisiebner 2019). Personal factors, in particular personal interests, have proven to be empirically proven and particularly strong in explaining the choice of a particular occupation. These in turn are influenced by factors such as self-efficacy beliefs, stereotypical ideas or images, or are in a mutual interplay (Lent 2013; Gottfredson 2006). These personal factors are in turn shaped by social and environmental influences (Patton and McMahon 2014). For example, parents‘ behavior and their own social or occupational identities, as well as peers and other role models, can exert some influence on career choice decisions (S. D. Brown and Lent 2020). In addition, increased knowledge and specific knowledges about certain occupations can be counted among the personal factors of career choice (Patton and McMahon 2014). It is assumed that certain occupational preferences occur more strongly when the knowledge about these occupations is assessed as particularly high by the occupational choosers (Taskinen 2010). For craft occupations, it could be shown that incorrect knowledge about these occupations leads to a worse evaluation of the occupational images (Mischler 2017). For caring occupations, it was also found that young people are significantly less likely to prefer them if they assess their knowledge about these occupations as poor (Matthes 2019). One goal for a self-determined career choice should therefore also be to reduce and correct erroneous perceptions about professions or job profiles.

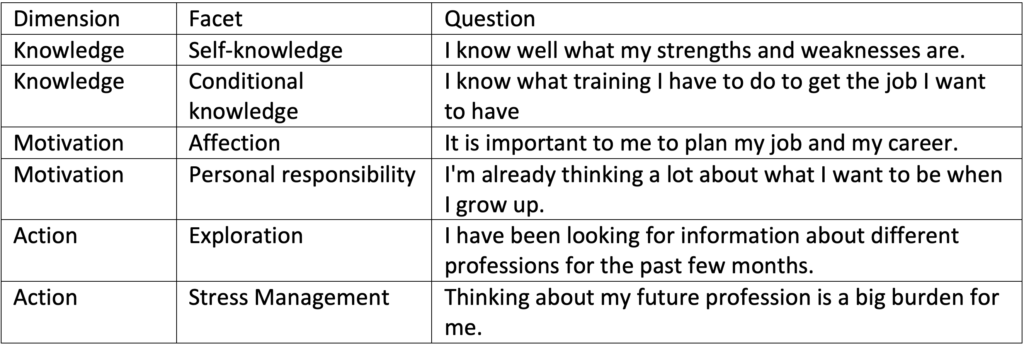

For young people, the decision for a particular occupation is probably the most important decision-making situation with very strong effects on their future career. Moreover, the decision to choose a profession takes place in a phase of growing up and thus in a stage of life that is associated with a great deal of uncertainty (Dedering 2000). Support in the process of career orientation should therefore ideally lead to a strengthening and promotion of career choice competence (Sommer et al. 2018). This refers to the „ability of school leavers to make a largely rational and, as far as possible, independent decision in favor of school-based or in-company training in a specific occupational field and to translate this decision into action“ (Dibbern 1983). The concept of career choice competence can be subdivided and operationalized into the dimensions (1) knowledge, (2) motivation, and (3) aspects of action (Lipowski et al. 2015). Table 1 provides examples of concrete questions on the individual dimensions and facets of career choice competence.

Measures with the intention of making a successful contribution to career choice competence should therefore increasingly target these areas.

In the following, in addition to the scientific findings already discussed, experiences are shared that the start-up Shadow Your Future, which deals with the topics of career orientation and securing young talent, has been able to gain.

The balance between online and offline

Nowadays, young people mainly inform themselves via the internet and social media. The flood of information reveals numerous career options, but this does not necessarily make it any easier to make a decision. At this point, young people know that there are many career paths, but the question remains as to which is the right one. In order to find out exactly that, practical insights play a central role. The young person gets a feeling for what he or she actually enjoys: working in an office or in the fresh air? Manual work yes, or no? Do I prefer working in a large or small company? Do I like working with people or alone? Do I like the working atmosphere in the company? This is exactly what you need to find out in order to be able to consider planning your own career in the next step and to be able to start your professional life without any worries. If we look at the way in which information is obtained today and, in the course of this, the challenges faced by young people, one thing quickly becomes clear: companies have to draw attention to themselves „online“ and generate enthusiasm „offline,“ i.e., in personal contact.

What the balance between online and offline can look like becomes clear when one considers the perspectives of the four stakeholders who play an important role here:

Generation Z needs to be addressed differently today. Young people are very active on social media, have grown up with it and make decisions in a very short time. They usually pay less attention to longer online contributions, whether text or video. A greater effort in obtaining information, such as clicking through on a website, is met with little enthusiasm. Technical terms and stated requirements in job advertisements often deter young people from applying at all. If you want to attract the attention of young people, you have to address them in a way that is appropriate for the target group in order to increase the chances of visibility.

Companies, on the other hand, as the second stakeholder, often do not have the capacity or know-how to build up their own social media presence and strategy and to implement an approach that is suitable for Generation Z. Numerous recruiting measures do not show the desired results due to high wastage and the way they are addressed. Furthermore, measures to recruit young people are usually too short-term and are therefore not designed for sustainability. Young people must be enthused at an early stage in order to win them over for future training. Measures that result from a lack of applicants for the current year are often not effective, but are all the more cost-intensive.

Parents play a major role as another stakeholder, as has already been made clear. They usually offer young people initial ideas and insights from their experience and their circle of acquaintances when it comes to various occupational profiles. They are often also the ones who motivate their children to take advantage of practical insights and demonstrate their importance. Therefore, it is of great importance to pick up parents in the career orientation phase, to make them aware of career profiles and to involve them. Parents with a migration background often face language barriers that make it difficult to involve them in the process of choosing a career. This challenge also needs to be addressed. In this context, cooperation with schools is essential. Schools not only serve as a mouthpiece to parents, but are also in direct contact with young people on a daily basis.

The fourth stakeholder to be mentioned is teachers. They are often extremely busy with individual work in the context of career guidance and can therefore only offer limited support. However, they are also of great importance when it comes to direct exchange with young people.

If we consider the actors described above and their roles in the context of career guidance, the following strategies can be used to achieve an optimal balance between online and offline measures: Online, companies should focus on social media presence, showing early, non-binding career insights, and addressing students in a way that is appropriate for them. Offline, the involvement and advice of parents, as well as cooperation with schools and teachers, play a central role in introducing young people to practical insights and thus supporting them in their career orientation.

Shadow Your Future is an example of a young start-up company that focuses on the challenges described above and presents a modern concept for career orientation and securing young talent. It also addresses the problems of lacking capacity and know-how in companies. The online platform brings young people and companies together via a short, practical career insight, a so-called „shadowing“. The young person accompanies an employee for one or more days, looks over his or her shoulder as if he or she were his or her „shadow,“ and thus experiences everyday working life up close. Shadow Your Future offers a virtual place where both sides can meet online. Companies can offer shadowing there, the formulation suitable for students as well as the application via social media are taken over. This gives young people the opportunity to find out more about shadowing and companies online and to gain a deeper insight offline. Since regular exchange with parents and schools cannot usually be provided by companies, this is also part of the offline strategy implemented by Shadow Your Future. A central platform also saves teachers a lot of individual work and young people can be supported much better in their career orientation phase.

In a next step, we would like to specifically address individual challenges in this context that young people and companies are particularly often confronted with.

Challenges of Generation Z & Companies in the Context of Career Orientation.

Let’s assume a student has become aware of a company and has asked for a practical insight, independently or with the support of a teacher or parent. Where do we go from here?

Shadow Your Future’s experience has shown that after a successful approach and request for a practical insight, it is often the way of communication between companies and young people that is crucial. This applies both to the preparation, e.g., in the context of the appointment arrangement, and to the practical insight per se. When looking at how the company contacts the young person to arrange an appointment, it is important to note that this can be a challenge for the young person. Nowadays, young people communicate mainly via chats. The formulation of a formal e-mail to a company is often associated with great uncertainty. Help must be provided by parents, teachers or support services such as Shadow Your Future. Young people still lack experience and a sense of the time frame within which they are expected to respond. The communication method is often the reason why companies and young people do not even come together in later application processes. This applies, for example, to the response time of the students or their use of language. It is therefore all the more important for students to familiarize themselves at an early stage with the customs and expectations of appropriate communication methods within the corporate world.

Once the communication hurdle has been overcome and an appointment has been made for a practical insight, successful shadowing stands and falls with this: How can companies generate enthusiasm for a profession and the company in a short period of time? There are four main aspects on which a special focus should be placed:

- Ice breaker:

Young people are often shy and insecure at the beginning. In order to make the best use of the time and to get to know the young person better, a relaxed atmosphere must be created in which the young person feels comfortable asking questions and being himself. It often helps to involve a trainee or young employee as a companion on this day. The small age difference with the student can break the ice and a person who has not been with the company for long can empathize with the student better than someone who has been part of the company for several years.

- Everyday relevance:

Young people often find it difficult to put the company’s product or service into context and thus find it difficult to identify with it. However, this is particularly important for today’s generation. In order to better pick up and inspire young people, products and services must be placed in an everyday context: Where can I find the product or service in everyday life? What concrete examples are there? Why is it important?

- Get involved:

If the job description allows it, experience has shown that it is more effective to let the young person solve a task independently. On the one hand, this increases the fun factor for the young person and, at the same time, gives companies the opportunity to identify strengths and weaknesses. It is possible that the young person is better suited for the job description or for another area within the company. Furthermore, a task to be solved independently gives the young person the opportunity to ask questions and exchange ideas.

- Training opportunities:

If the student turns out to be a suitable candidate, the training opportunities in the company should be discussed at the end of the practical insight. Ideally, a trainee or student can talk to the young person again in person afterwards to give him or her an authentic perspective and answer any questions. Information material, a certificate about the career insight and a sporadic exchange help to stay in contact and increase the chance that the young person will apply for an apprenticeship or a degree program after graduation.

In a constantly evolving environment, all communication processes, including the methods used to establish contact between stakeholders, must always be adapted to external conditions.

The challenges described in the context of the shortage of skilled workers and career orientation are multifaceted and very complex. If one wants to counteract these challenges, various stakeholders must be involved. A long-term and sustainable strategy plays a central role here. Young people need to gain an early insight into a variety of careers and companies, and companies need to raise awareness and enthusiasm at an early stage. Services such as those offered by Shadow Your Future provide an adequate approach to solving this problem and are an example of how job shadowing can be used to counteract the shortage of skilled workers.

Sources

Anger, C.; Kohlisch, E.; Koppel, O.; Plünnecke, A. (2021): MINT-Herbstreport 2021. Mehr Frauen für MINT gewinnen – Herausforderungen von Dekarbonisierung, Digitalisierung und Demografie meistern, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, Köln.

Brown, S. D. & Lent, R. W. (Hrsg.). (2020).:Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, Hoboken.

Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2022): Monatsbericht zum Arbeits- und Ausbildungsmarkt. In: Berichtie: Blickpunkt Arbeitsmarkt. Online: https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/datei/arbeitsmarktbericht-marz-2022_ba147413.pdf, (20.06.2022)

Calmbach, M.; Flaig, B.; Edwards, J.; Möller-Slawinski, H.; Borchard, I.; Schleer, C. (2020): Wie ticken Jugendliche? 2020. Lebensweilten von Jugendlichen im Alter von 14 bis 17 Jahren in Deutschland. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

Dedering, H. (2000): Einführung in das Lernfeld Arbeitslehre, München.

Dibbern, H. (1983): Berufsorientierung im Unterricht: Verbund von Schule und Berufsorientierung in der vorberuflichen Bildung. Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, 16, 437–449.

Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag e.V. (DIHK) (Hrsg.) (2021): DIHK-Report Fachkräfte 2021. Fachkräfteengpässe schon über Vorkrisenniveau. Online: https://www.dihk.de/resource/blob/61638/9bde58258a88d4fce8cda7e2ef300b9c/dihk-report-fachkraeftesicherung-2021-data.pdf, ( 20.06.2022).

Dreisiebner, G. (2019): Berufsfindungsprozesse von Jugendlichen: Eine qualitativ-rekonstruktive Studie, Wiesbaden.

Fitzenberger, B. Gleiser, P.; Hensgen, S.; Kagerl, C.; Leber, U.; Roth, D.; Stegmaier, J.; Umkehrer, M. (2022): Der Rückgang an Bewerbungen und Probleme bei der Kontaktaufnahme erschweren weiterhin die Besetzung von Ausbildungsplätzen. Online: https://www.iab-forum.de/der-rueckgang-an-bewerbungen-und-probleme-bei-der-kontaktaufnahme-erschweren-weiterhin-die-besetzung-von-ausbildungsplaetzen/, (20.06.2022).

Gottfredson, L. S. (2006): Circumscription and compromise. In: Greenhaus, J. H. & Callanan, G. A. (Hrsg.), Encyclopedia of career development (S. 167–169). Thousand Oaks.

Hüther, M. (2017). MINT-Frühjahrsreport 2017 – MINT-Bildung: Wachstum für die Wirtschaft, Chancen für den Einzelnen. Online: https://www.iwkoeln.de/fileadmin/publikationen/2017/339805/Statement__Huether_MINT_Fruehjahr_2017.pdf, (20.06.2022).

Köcher et al. (2019) : Die McDonald’s Ausbildungsstudie 2019. Kinder der Einheit. Same same but (still) different! Online: https://karriere.mcdonalds.de/docroot/jobboerse-mcd-career-blossom/assets/documents/McD_Ausbildungsstudie_2019.pdf, (20.06.2022).

Lent, R. W. (2013): Social Cognitive Career Theory. In: Brown, S. D. & Lent, R. W. (Hrsg.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, S. 115–146, Hoboken.

Lipowski, K., Kaak, S., Kracke, B. & Holstein, J. (2015): Handbuch schulische Berufsorientierung. Anhang A. Fragebogen Berufswahlkompetenz. Online: https://www.schulportal-thueringen.de/tip/resources/medien/33419?dateiname=Materialien_189_Anhang_A_-_Fragebogen_Berufswahlkompetenz.pdf, (20.06.2022).

Matthes, S. (2019): Warum werden Berufe nicht gewählt? Die Relevanz von Attraktions- und Aversionsfaktoren in der Berufsfindung. Berichte zur beruflichen Bildung. Bonn.

Mischler, T. (2017): Die Attraktivität von Ausbildungsberufen im Handwerk: Eine empirische Studie zur beruflichen Orientierung von Jugendlichen. Berichte zur beruflichen Bildung. Bielefeld.

Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2014): Career Development and Systems Theory: Connecting Theory and Practice. Rotterdam.

Schnetzer, S. (2021): Die Generation Z richtig ansprechen. Mit dem Generationenmodell ABBAS zur zielführenden Zielgruppenkommunikation. Online anzufordern: https://simon-schnetzer.com/generation-z/ (20.06.2022)

Sommer, J., Ratschinski, G., Eckhardt, C. & Struck, P. (2018): Berufswahlkompetenz und ihre Förderung: Evaluation des Berufsorientierungsprogramms BOP. Bonn.

Taskinen, P. (2010): Naturwissenschaften als zukünftiges Berufsfeld für Schülerinnen und Schüler mit hoher naturwissenschaftlicher und mathematischer Kompetenz: eine Untersuchung von Bedingungen für Berufserwartungen. Online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:8-diss-56859, (16.08.2020).

About the authors

Jill Hollender is the founder and managing director of Shadow Your Future GmbH. After graduating from high school, she studied business administration with a technical qualification in mechanical engineering at the Technical University of Kaiserslautern and subsequently completed her dual master’s degree at Leeds University in cooperation with IBM. By visiting numerous companies on a study tour to the USA in 2018, J. Hollender grew a passion for supporting young people in their career orientation. During various roles at IBM in project management and sales, she launched Shadow Your Future and is now working full-time for her startup.

Manfred Mohr graduated with a doctorate in economics in the field of vocational behavior and gender research. Currently, he works as a second community school dean and as a lecturer at the Institute for Economics and its Didactics at the Karlsruhe University of Education. His main research interests are in the areas of vocational development and related topics of economic education.